A Portrait of Female Pain, Rebellion, and Refuge

Stoking the flame of mental anguish and abuse, Anita Desai’s 1977 novel Fire on the Mountain is as much about the silent suffering of women as it is about seeking solitude, rebellion, and selfhood. It stands as one of the most celebrated works of post-independence Indian fiction, revealing the interior lives of women with remarkable restraint, honesty, and power.

A Glimpse Into Women’s Inner Worlds

Desai gives readers a layered insight into the lives of women across different age groups and circumstances. The novel carefully peels back the façade of domestic roles to uncover emotional landscapes usually hidden from public view. With prose that is both precise and poetic, she captures the textures of female existence—often defined by repression, sacrifice, and a desperate yearning for independence.

Nanda Kaul: The Quiet Rebellion of Silence

The story begins with Nanda Kaul, an elderly, widowed woman who has retreated to the hills of Kasauli. But her retirement is not merely from work—it’s from society, marriage, and the exhausting performance of perfection she once maintained as the wife of a Vice-Chancellor.

Now, living in semi-neglect in her crumbling home "Carignano," Nanda embraces the disarray and wildness. It becomes a form of radical self-care—a life finally lived on her own terms. Her solitude is not loneliness, but liberation from the social expectations that had once drained her.

Enter Raka: A Child Shaped by Silence

Nanda’s retreat is disrupted by the arrival of her great-granddaughter Raka, a sickly and withdrawn child sent away from her abusive home. Her mother, still entangled in a violent marriage, must join her diplomat husband in Geneva to attempt a reconciliation.

Raka, too, seeks solace in the wild. She isn’t interested in attention or approval—she is fiercely independent, exploring the hills and forests on her own. Her detachment resonates with Nanda, and though few words are exchanged, a silent, emotional thread links the two.

Layers of Trauma: Abuse Wears Many Faces

Desai’s genius lies in her nuanced portrayal of how abuse and suffering manifest differently:

Nanda Kaul

Her trauma is psychological. Years of performing the “dutiful wife” in a loveless, dishonest marriage have numbed her emotionally. Her husband's affair and her identity reduced to hostess and homemaker reflect the invisible suffering many women endure under the guise of social prestige.

Raka

Raka’s pain is rooted in childhood. The neglect and violence she witnesses at home begin to erode her trust and shape her worldview. Her silence is her shield, and her solitude, her rebellion. She represents the intergenerational trauma that silently persists.

Ila Das

A close friend of Nanda, Ila Das is a tragic figure of female resilience in a world that refuses to acknowledge her worth. Despite her commitment to social work—fighting child marriage and patriarchy—she faces degradation, poverty, and ultimately violence. Her fate is a chilling reminder of what happens to women who step outside patriarchal bounds.

The Novel's Message: Survival, Solitude, and Shared Suffering

Fire on the Mountain is unflinching in its portrayal of female sorrow. But it is also deeply introspective, offering moments of tenderness, connection, and quiet triumph. The novel doesn’t wrap up in optimism—but in a fierce act of defiance. The final gesture—though subtle—becomes a space where all the characters' silent burdens find voice. It’s not a clean resolution, but rather, an earned moment of agency.

What Desai Leaves Us With

Desai refuses to sugarcoat the trauma her characters face. She shows how female identity is often shaped by societal expectations, sacrifices made in silence, and emotional labor rendered invisible. Nanda Kaul is a mirror to many women—outwardly composed, inwardly fragmented.

Fire on the Mountain is not just a novel; it’s a testament to generations of women who live with the scars of silent suffering. It warns us of how trauma, when unaddressed, travels down generations—as in Raka’s case. And it mourns women like Ila Das, crushed for trying to assert their autonomy in a male-dominated world.

A Celebration in Grief

Despite its somber tone, the novel is also a celebration—not of pain, but of survival. Desai suggests that women do have a place where they can be fully themselves. That place may not lie in society’s confines, but in wildness, in solitude, and in stories like this one.

In Fire on the Mountain, the mountain becomes a metaphor: remote, untamed, and healing. It’s where women can reclaim their voices—even if only in whispers—and rediscover who they are when no one is watching.

Like our content? Please support us by sharing and upvoting!

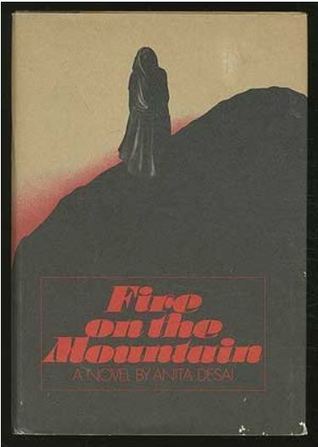

Image Credits: Goodreads